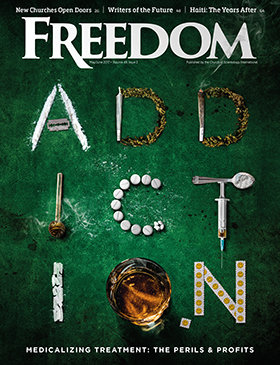

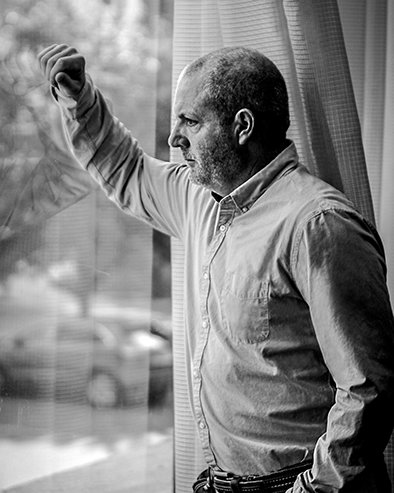

A Southern lawyer tells how we got here, and how he hopes to use a forgotten state law to rescue the country from the opioid epidemic.

Huntington, W.Va.—He’s a small-town attorney—and he ran for president of the United States.

He also took a local law that was intended to keep the noise down and is using it to sue for billions of dollars. And he hopes doing it will save a community, an entire country and a generation.

He is trying to pull a rabbit—out of a thimble.

“It could be magic, or it could be tragic,” said Paul Thomas Farrell Jr. “But at least we’re trying.”

Farrell grew up as the son of a judge in West Virginia, when coal mines were busy, the population in and around Huntington was at 100,000, and most everyone knew everyone else’s business—and that was okay. Back then, people took care of each other.

A smart, affable and proud West Virginian, he went away to college (Notre Dame), came back to Morgantown for law school, then returned to Huntington and saw the town falling down around him. As the coal mines closed, he saw out-of-work and injured people begin to rely on pain pill prescriptions, by the carloads.

Some sold them to others, some took them themselves—and seemingly half the county became addicted. When the pills became harder to get, heroin was suddenly easy to get—even more addictive and more deadly. Friends and neighbors were dying, or losing everything they owned.

“We have to inoculate our kids. … We have to teach them their mom and dad’s pain pill bottle in the medicine cabinet is just as dangerous as a crack pipe.”

Farrell ran for U.S. President in 2016 as a Democrat, but only registered as a candidate in his home state to bring attention to the “economically gutted regions of the state.” He came in third in the state primary, with 9 percent of the vote, behind Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton.

Farrell still wants to take care of his people. And like any good Southern lawyer, he has a story to tell. Hearing it is like getting directions from a local: it rambles, but it’s worth the trip.

The story begins early last year at a breakfast table. While pondering on what a small-town lawyer with federal court experience could do, he recalled an old state statute, put on the books decades ago to protect townsfolk against nuisances: it prohibited things like junk piles in people’s yards and noisy bars staying open late. It called for the responsible parties to abate the issue, that is, to remove the problem—and pay for damages.

And he decided he could use that law to stop the opioid epidemic.

“The statute is a West Virginia statute,” he told Freedom late one Tuesday afternoon, as he sat in shorts and a polo shirt in his Huntington office, his ground floor window facing a quiet downtown street. “It’s unlawful conduct that gives rise to a public nuisance. The unlawful conduct that we’re alleging is a violation of federal law.” The federal law he refers to holds the wholesale distributors responsible for reporting unusual activity—which they didn’t.

The problem began, Farrell said, when we turned “our American pharmaceutical industry loose on opium. Pharmaceutical-grade heroin, and by God, it rocked the world. We let the genie out of the box.”

How it happened

In 1970, Congress enacted the Controlled Substances Act, Farrell explained, to regulate the production and sale of narcotics, “because they knew if the genie got out of the box they would never get it back in.”

“But the interesting thing the Congress did was they stripped away from the manufacturers the right to sell direct,” Farrell said, since they knew they would sell as many as people would buy, “and they decided that laissez-faire version of economics was probably not the best idea with controlled substances.”

Congress created a “middleman,” the wholesale distributors. “I call them Willy Wonka’s Golden Ticket,” Farrell said. “There’s only 800 of them in the country,” he said. “Three of them now dominate 85 percent of the market share: Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen and McKesson. Each of them generates over $100 billion a year; each of them has climbed the Fortune 500 rankings, in direct parallel to a skyrocketing relationship to the sale of OxyContin.

“McKesson’s now No. 5 in the country, 11 in the world. They’re delivery vans, but Congress created this delivery van, with one job and only one job,” he said, getting to the meat of the story.

The distributors’ mandated task was to detect suspicious orders—any increase of 15 percent or more—and report them to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) monthly. Yet West Virginia, and eventually other areas, saw prescription increases of 100, 200 even 900 percent or more in some places, but no reports were filed.

In 2001, Farrell noted, a government oversight agency reviewed the DEA’s reports on OxyContin and determined that the DEA was also negligent. At the time, he said, DEA officers were “underfunded, understaffed and ill-equipped to handle the volume. We’re talking about 30 million transactions.”

Over the next few years, the DEA began going after distributors. One of the distributors’ wholesale centers got caught selling a 500 percent increase in opioids to just five pharmacies in Florida, which all became well-known “pill mills,” facilitating in the process of illegal street sales of opioids further up the East Coast. When the DEA prohibited that center from selling to those five pharmacies, the distributor simply supplied those pharmacies from a different center.

“[Then] the DEA agent says, ‘Are you kidding me? You’re still selling?’ So they hammered them,” Farrell said. The DEA hit Cardinal with a $44 million fine and revoked the registration of that facility.

That type of fine, Farrell said, is generally paid instead of being appealed, because the wholesale distributors do not want to have to put their financial figures into public records. “For instance,” he said, “McKesson paid a $150 million fine in January of [2017], and their stock price didn’t change.” In other words, these companies are making so much money that a $150 million fine is barely noticeable to their investors.

A majority of pill mills have since been shut down, and the DEA mandated a reduction in the number of pills that manufacturers are allowed to produce by 25 percent in 2017, and another 20 percent for 2018. Some manufacturers, including Purdue Pharma, makers of OxyContin, have already significantly reduced the number of salespeople promoting opioid pain pills.

The Second Tier of the Problem

“When the pills aren’t available anymore, … it goes to heroin. The heroin epidemic has just started,” Farrell warned.

“Everybody wants to [blame] the manufacturers, nobody’s really picked up yet on the role the distributors have played. These three companies [McKesson, AmerisourceBergen and Cardinal Health], … they’re just as big or bigger than Purdue. And they don’t ‘make’ anything, they don’t have labs and scientists. They have one job: the volume.

“So … what I’m going to do is make them abate the public nuisance.”

Farrell got together with community leaders and made a plan for what is needed to fully repair the damage done by the opioid epidemic, and prevent it from ever happening again. He sued not just the big three distribution companies, but also Walgreens, CVS and a total of 24 distributors.

He has a formula for what it will take to recover. The first step, he said, is education.

“I can’t overemphasize this. We have to inoculate our kids. I don’t mean high school kids, I mean grade school kids. We have to teach them their mom and dad’s pain pill bottle in the medicine cabinet is just as dangerous as a crack pipe.” He wants board of education and health department funding, as well as drug abuse partnership funding. He estimates the cost at $5 million a year for 10 years—in each of the seven counties, totaling $350 million—for step one. The abatement would be well over a billion dollars. “They can afford it,” he says confidently. “That’s the only way you effectuate change in the United States of America, is by impacting the bottom line.”

Let the Judge Decide

Farrell’s case, filed in 2017, was recently placed in a massive Multi-District Litigation (MDL) in Cleveland, along with some 400 others filed by cities, counties and Native American tribes. The intent is for similar cases to be heard under one jurisdiction to speed up the discovery process and pretrial rulings.

The MDL is being heard by U.S. District Judge Dan Polster, a former assistant U.S. attorney with 20 years of experience as a federal judge, who is known to resolve cases quickly. Though he recently scheduled three of the more than 400 cases in the MDL for trial in 2019, he has suggested that attorneys be thinking of settlement options. He also ordered that the DEA turn over their confidential records detailing the exact number of prescription opioids delivered to every city and county in the country.

Despite having paid settlements in similar individual cases, Purdue Pharma denies allegations and says it is “dedicated to being part of the solution.” A Purdue spokesman engaged in a 15-minute “off-the-record” conversation with Freedom, promising an “on-the-record” statement and explanation—but never called back or answered subsequent calls. Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen have also each settled multimillion-dollar consumer protection lawsuits, Farrell said—though they too, deny any wrongdoing.

Cardinal Health’s executive chairman, George Barrett, apologized for his company’s practice of saturating West Virginia with painkillers, but denied it had anything to do with the country’s opioid epidemic.

Barrett told a Congressional subcommittee investigation, separate from the MDL, that “with the benefit of hindsight, I wish we had moved faster and asked a different set of questions. I am deeply sorry we did not.” But when asked if his company, and four other distributors, contributed to the current crisis, he replied, “No sir, I do not believe we contributed.”

Even under the MDL, Farrell, one of three co-lead attorneys, sees his case as slightly different. As he explained, suing a drug manufacturer frames the case as a “product liability case—you have to show design defect, or labeling defect,” he said. “I don’t have to prove any of that. Mine is public nuisance,” Farrell said, sounding like practice for a closing argument. “You broke the law in West Virginia. … Let’s just pick a random number. … You broke the law 10,000 times. I just have to prove it once. You helped create a public nuisance that resulted in drug abuse, addiction, morbidity and mortality—now you have to abate it. How do you abate a public nuisance like that?

“It’ll cost you about a billion dollars. And you can write a check.”