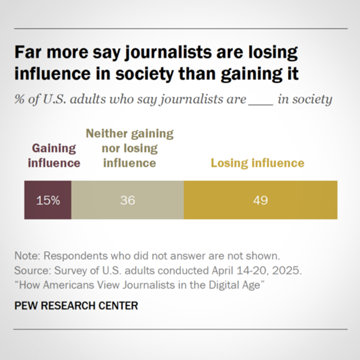

In a moment when factual, reliable reporting seems more vital than ever, these numbers, published by the Pew Research Center on August 20, are cause for concern. That’s because the erosion of trust in journalism doesn’t just threaten individual outlets—it chips away at a democracy’s ability to function.

A majority of Americans—59 percent—say journalists are extremely or very important to the wellbeing of society, and another 31 percent say they’re somewhat important. Still, 49 percent believe journalists are losing influence, with just 15 percent saying they’re gaining clout.

Journalism hasn’t lost its purpose—but Americans want the profession to rebuild trust.

One participant in his 30s summed it up this way: “There are a handful of journalists, the ones that we say we trust, that I think are doing the right thing.… But the others … are all about clicks, eyeballs, money.… They don’t necessarily mind tweaking the truth to suit their audience or their advertisers.”

Another factor emerges: What counts as a “journalist” in the first place is far from settled. Nearly 8 in 10 Americans (79 percent) say someone writing for a newspaper or news website is a journalist—but majorities do not extend that label to newer formats: 46 percent say hosts of news podcasts are journalists, 40 percent say the same of newsletter writers, and just 26 percent view social media news posters as journalists.

Focus groups captured the confusion—and frustration—around these shifting boundaries. A woman in her 20s observed: “I feel like anyone can do it.… There’s a lot of people out there just starting their own channels.… It can make it feel like a journalist isn’t as important. Although, they are the ones that are really skilled in that job.”

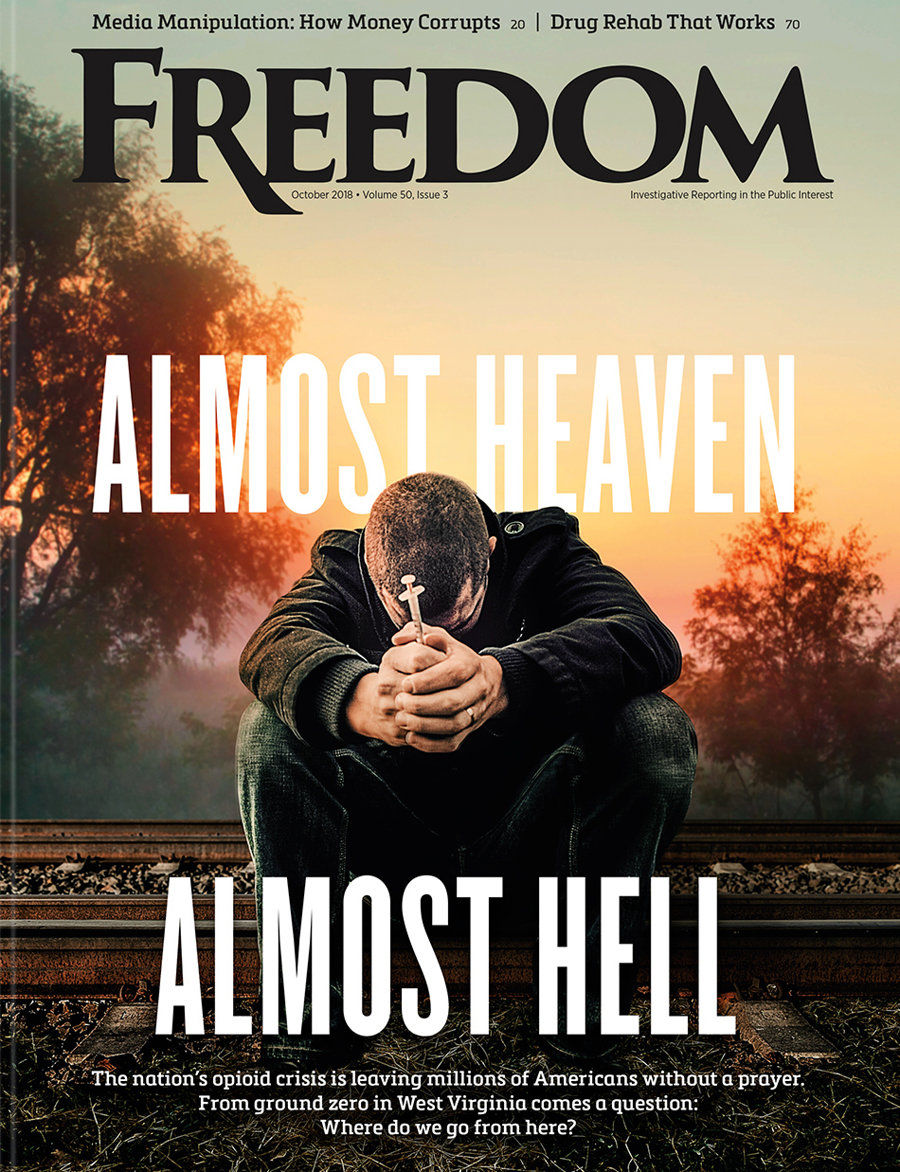

That skill is precisely what audiences believe is being eroded by undisclosed conflicts of interest. A case in point is The Outer Banks, a secret Facebook group devoted exclusively to anti-Scientology bigotry, which has counted among its members not only expelled individuals and rabid anti-Scientologists but even reporters from mainstream outlets like Dana Kennedy of the Daily Mail and Kevin Dugan of The Wall Street Journal. These are not passive observers: Both have sought to “cover” Scientology in their reporting, even while participating in a hate group explicitly devoted to the religion’s destruction. Their membership in a forum where violence against parishioners is openly discussed (posts include “Scientology must be smashed to pieces” and “shut them down or make them suffer”) is a stark violation of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics—and proof that concerns about bias are grounded in ugly reality.

Earning public faith requires more than credentials—it depends upon returning to journalism’s core.

The tension between the skills journalism requires and the flood of online content—including propaganda from bigoted reporters passed off as “news”—sets up the larger question: What do people want from their news? A remarkable 93 percent say honesty is important, 89 percent point to intelligence and 82 percent to authenticity. But authenticity means different things to different people—ranging from being “who they say they are,” to “minimum Pinocchios” (a nod to the Washington Post’s fact-checking scale, where more Pinocchios signal bigger lies).

When it comes to journalists’ core responsibilities, Americans tend to set aside questions of style or authenticity and focus instead on basic functions of the job. They believe their news sources should report accurately (84 percent) and correct misleading information from public figures (64 percent), while fewer expect other roles: 41 percent want watchdog functions, 34 percent say giving voice to underrepresented people is important, and just 32 percent want community advocacy out of journalists.

Concerning qualifications, a journalist’s deep knowledge of a particular topic matters far more than credentials: 70 percent say it’s very or extremely important; by contrast, only 31 percent care if a news provider is employed by a news organization, and just 25 percent say journalism degrees matter.

Verbal transparency is also valued—66 percent say it’s extremely or very important for journalists to share how they handle mistakes, yet many complain that retractions often get buried or hidden. As one man in his 60s put it, newspapers will “put something on the front page that’s not right, and then [the retraction of] the mistake will be on page 820 or something.”

Public skepticism of journalists doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Just weeks before Pew published its survey, a Gallup report documented that overall confidence in institutions—including news media—remain near 46-year lows. Only around 28 percent of Americans express confidence in institutions ranging from Congress to newspapers.

One thing is clear from the results: Journalism hasn’t lost its purpose—but Americans want the profession to rebuild trust, which will mean becoming more transparent, responsive, accurate and authentic. They cherish honesty, knowledge, humanity and accountability and expect accuracy and fact-checking, while remaining wary of bias, blurred roles and performative narratives. And as institutional trust continues its downward drift, journalists face an ever-graver reckoning: Earning public faith requires more than credentials—it depends upon returning to journalism’s core by staying truthful, owning errors and elevating public interest above agendas and clicks.

Pew’s findings reveal the erosion of trust; the daily conduct of the press makes it undeniable. Journalism can either reckon with its failures of disclosure and integrity or risk becoming indistinguishable from the very partisans and propagandists it claims to expose and oppose.

If done well, journalism’s quiet revival, hinged on substance and authenticity, might just begin to reverse the slide and restore trust—one honest story at a time.