McKibban’s death wasn’t caused by a tainted drink or an unknown additive. Instead, it was ruled the result of toxicity from mitragynine, an addictive opioid-like compound found in kratom. His case now anchors one of dozens of wrongful death lawsuits filed across the US, turning a once-obscure herbal stimulant into the latest flashpoint in America’s war over drugs, regulation and corporate responsibility.

Despite years of warnings from the DEA and FDA, kratom has largely slipped through regulatory cracks.

At stake is not just another dubious wellness fad. Federal regulators warn that kratom’s concentrated byproduct—7-hydroxymitragynine (7-OH)—is up to 30 times more potent than morphine. In late July 2025, the Food and Drug Administration formally recommended that 7-OH be scheduled under the Controlled Substances Act, citing its opioid-like effects and addiction risks. Just days later, Louisiana outlawed all kratom products; Florida banned 7-OH; and Orange County, California, passed its own restrictions, dubbing the substance “legal morphine.”

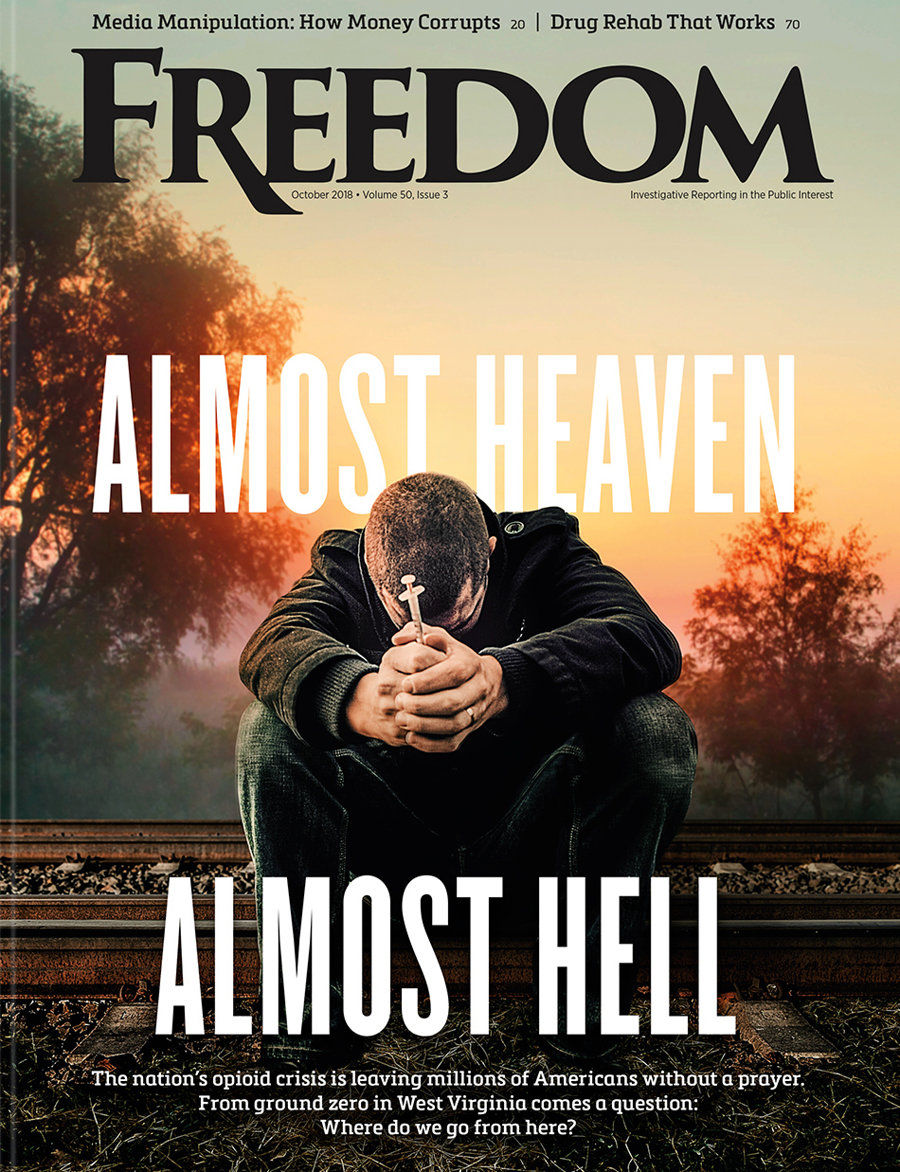

But with 1.6 million to 1.7 million Americans reporting kratom use in national surveys, and research showing up to a third suffer serious side effects like seizures, heart problems or organ damage, regulators fear a “fourth wave” of the opioid crisis is brewing. Lawsuits, meanwhile, are exposing deceptive marketing and fueling public outrage.

Kratom, or Mitragyna speciosa, has long been chewed or brewed as tea in Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia to relieve pain or stay awake during long shifts. But the kratom now sold in US gas stations bears little resemblance. As Florida resident Sheldon Jernigan put it, “It was a super strong, very potent thing that took me on the wildest ride in my life.”

Today’s products—capsules, gummies, flavored shots—are often chemically fortified with 7-OH, the byproduct that turns kratom from a mild stimulant into what University of Florida scientist Christopher McCurdy likened to “a pure opioid,” comparing the difference to “drinking a Miller Lite versus drinking 12 ounces of Everclear.”

Families blindsided by kratom’s dangers are increasingly turning to the courts, exposing a pattern of deception that runs through their lawsuits. Among the highest-profile cases:

- Krystal Talavera (Florida, 2021): Collapsed and died after using a kratom product called “space dust.” Her family won an $11 million default judgment against Grow LLC (Kratom Distro) after the company failed to defend itself.

- Matthew Torres (Oregon, 2021): Collapsed and died foaming at the mouth after using “Real Kratom.” His mother’s $10 million lawsuit accuses sellers of deceptive labeling and compares the industry to a drug cartel.

- Patrick Coyne (Washington, 2023): Jury awarded $2.5 million after his death from acute mitragynine intoxication, marking the nation’s first contested kratom trial where a verdict was rendered after arguments and evidence.

The suits allege companies disguise kratom products as “for research purposes, not for human consumption,” use shell corporations to import them, and omit warnings about overdose or addiction. “Kratom manufacturers, distributors and sellers try to conceal their ownership and financial activities to avoid accountability,” according to Torres’ attorney.

A growing number of class actions echo those claims, charging fraud, failure to warn and deceptive “all-natural” marketing.

Medical literature now documents kratom’s harms with increasing precision. The CDC linked it to 152 deaths between 2016 and 2017; poison control calls linked to the substance in Texas alone rose from 83 in 2019 to 123 in 2022, with at least five deaths in the state. Nationally, poison centers logged 1,807 kratom exposures between 2011 and 2017, a number that has risen sharply since.

Adverse effects range from seizures and psychosis to liver failure, high blood pressure and respiratory depression. In some extreme cases, long-term users even developed blue-tinted skin, possibly due to kratom’s impact on dopamine and melanin production.

For Jernigan, the Florida man who got hooked on 7-OH, detox was more crippling than anything he ever experienced coming off fentanyl and heroin. “It’s marketed in these bright-colored packages,” he warns, adding: “It’s towards kids. And what I really thought about is—I have children.”

Despite years of warnings from the DEA and FDA, kratom has largely slipped through regulatory cracks. In 2017, the DEA tried to schedule it as a controlled substance before retreating under political pressure. More recently, the American Kratom Association lobbied Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry to veto legislation in the state Senate banning kratom sales in gas stations and convenience stores. That effort failed and the governor signed the bill into law on June 4. Since then, a patchwork of state and local bans has emerged: Seven states outlaw kratom outright, while others, like California, cap 7-OH potency at 1 percent—a level regulators note is in line with natural concentrations in the leaf, designed to preserve access to traditional kratom while shutting down the chemically boosted extracts most linked to addiction and overdose.

Louisiana’s new law, which became effective August 1, classifies kratom as a Schedule I controlled substance—the same category reserved for heroin and LSD. An August 13 emergency rule announced in Florida makes 7-OH possession a felony. “Due to the danger posed to the public, Florida is taking 7-OH off the shelves immediately,” said Attorney General James Uthmeier.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., himself a former heroin addict, framed the federal push bluntly: “They’re marketing them to children: They’re gummy bears, they’re bright colors, they’re candy-flavored. This is really a sinister, sinister industry.”

For critics, the story of kratom feels all too familiar: a “natural” product marketed as safe, then quietly spiked, mislabeled and sold in neon packaging to unsuspecting consumers. Lawsuits pile up, regulators scramble and grieving parents demand answers.

Dr. Robert Levy of the University of Minnesota draws the opioid parallel starkly: Compared to kratom’s primary alkaloid, 7-hydroxymitragynine “is much more addicting and much more problematic,” he said, just days after FDA Commissioner Marty Makary declared in a news statement: “We need regulation and public education to prevent another wave of the opioid epidemic.”

As states ban bottles and juries award millions, the larger warning remains: In America’s unregulated supplement aisles, what looks like harmless powder in a shiny packet can be 30 times stronger than morphine. It seems the next epidemic won’t be arriving in needles and syringes—it might already be waiting at the checkout counter.