Strategically placed in the high-traffic corridor of Sandusky, Ohio—just miles from Cedar Point Amusement Park and a bustling sports complex—the message reached tens of thousands of holiday travelers over Memorial Day weekend.

But for those who know the horror behind the word, the message doesn’t just inform—it warns.

“The worst of it all is the trauma of being gaslighted by the very professionals I trusted and turned to for help.”

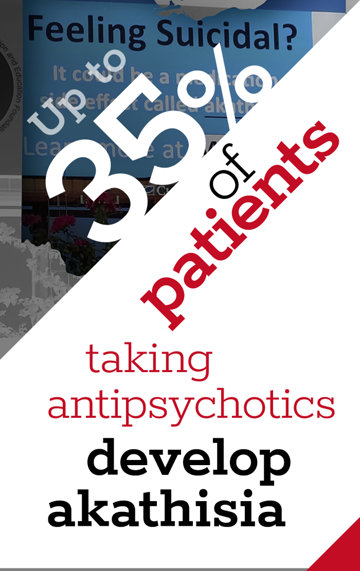

Akathisia—derived from the Greek term for “inability to sit”—is not a household term. Yet, according to a 2023 study, it’s a well-documented side effect of commonly prescribed drugs, from antidepressants to anti-nausea pills. The syndrome, often misidentified as anxiety or depression, can provoke unbearable inner restlessness, violent agitation and, tragically, suicide. As the pharmaceutical industry expands and prescriptions multiply, patient advocates warn: This silent side effect is claiming lives in plain sight, with doctors too often unaware and patients left misjudged—or worse, dead.

The Ohio public health campaign is the brainchild of the Chicago-based nonprofit MISSD—short for Medication-Induced Suicide Prevention and Education Foundation in Memory of Stewart Dolin. The organization has made it its mission to publicize the often-overlooked risks of akathisia, particularly as they pertain to psychiatric drugs and even commonly used medications.

“May is Mental Health Awareness Month,” said Wendy Dolin, the foundation’s founder. “Yet few—if any—suicide prevention and mental health nonprofits ever mention that medications can cause psychiatric symptoms and suicide.”

Dolin’s advocacy began after the 2010 death of her husband, Stewart, a successful Chicago attorney who had no prior history of disturbance. On an ordinary afternoon, shortly after lunching with a client, Stewart inexplicably left his office, walked to a train station he’d never used and jumped in front of an oncoming train.

“I kept saying, ‘What could happen in that hour?’” Wendy recalled in a 2021 interview. Her husband’s sudden death seemed inexplicable—until she began digging into the known side effects of Paxil, the antidepressant he had recently begun taking.

A nurse who saw Stewart shortly before his death told Wendy he was “pacing like a caged polar bear”—a textbook sign, she later learned, of akathisia.

It’s like a switch gets flipped, an authority on akathisia explained to her, referencing a phenomenon sometimes seen in Parkinson’s patients: fluid motion one moment, frozen the next. Akathisia, Wendy realized, could likewise trigger such drastic shifts—“the flip”—from calm to chaos. From coping to catastrophe.

Indeed, the 2023 study describes akathisia as a syndrome of relentless physical and internal agitation. “The individual may cross, uncross, swing or shift from one foot to the other,” the authors state, appearing to outsiders as “a persistent fidget.” But the internal experience is more than discomfort—it’s torment.

Some estimates suggest that up to 5 percent of people taking certain drugs may develop akathisia. A MISSD-produced video doesn’t mince words: “Death,” it declares, “can be a welcome result.”

And sometimes, the cause is not misuse. “Akathisia can occur even when medications are taken exactly as prescribed—or when they are stopped,” warns the foundation.

Still, unsurprisingly, drug manufacturers tread carefully around the word, trying to recast “akathisia” as something relatively benign. “The pharmaceutical industry has pretty much tried to water down the term,” said Wendy. “They’ll say it’s restless leg syndrome or emotional lability.” But “being moody doesn’t lead to ending your life.”

MISSD’s latest billboard campaign, which is expected to reach millions this year, owes its launch to an Ohio resident named Shelly, whose personal brush with the disorder nearly cost her her life.

Following the death of her mother from cancer, Shelly sought help from her family doctor, who prescribed Ativan, a Schedule IV controlled substance.

“Having an academic degree in the healthcare field and a previous career in the profession, I made sure to ask him about possible side effects,” Shelly said. “He casually described the medication as ‘like drinking two beers.’ That was it.”

What followed was five years of hell. Although she took the drug in small, physician-approved doses—four to five pills per month—Shelly’s symptoms steadily escalated. Severe insomnia. Heart palpitations. A surreal sensation of being “on a boat.” Unbearable sensitivity to light and sound.

Then came the night terrors—what she describes as “a constant state of terror,” complete with electric flashes in the brain and violent chest vibrations. “I asked my husband to put his legs over mine to reduce my shaking,” she recalled. “I thought he could see all my movements, but later realized that some of what I felt—the restlessness—was also internal.”

The condition grew so debilitating that she could no longer walk unaided, climb stairs or even read or listen to music. “The worst of it all is the trauma of being gaslighted by the very professionals I trusted and turned to for help,” Shelly said.

Her story is no outlier. As the list of drugs linked to akathisia grows—including drugs for depression, asthma, hypertension, nausea, even weight loss—experts and survivors alike are sounding the alarm.

“The lack of education about this condition is scary—especially given how many medications can cause it,” Shelly’s husband said. “This entire experience turned my wife’s life upside down and could have been prevented if doctors were properly trained and truly listened to their patients.”

The billboard stands where locals and tourists alike pass, most of them probably untroubled, on their way to roller coasters and baseball games. But for those who know the torment of akathisia, it stands as an indictment—not of what the psychiatric establishment forgets, but of what it refuses to admit: that in its so-called effort to “treat,” it readily destroys.

In a world saturated with prescriptions but starved for informed consent, MISSD’s urgent question hangs in the air, chillingly relevant to many:

“Is it akathisia?”